Over the past few months, the equation of love, caste, religion and marriage has come under close scrutiny. While love jihad played a role questioning this equation, the debate around honour killlings and ghar wapasi also led to many conundrums. But the most ignored aspect of all these politically-charged discussions has been a certain age-group of people and their contentions regarding love, marriage and societal acceptance in urban India.

In 1971, when Kenneth Keniston, one of the foremost social psychologists in America developed the idea of ‘youth’, he had pondered long and hard over this stage, that followed the period of adolescence. Contextualising the then resistance around the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War, Keniston had defined the stage to be a disconnect between one’s identity as a youth and the demands of the society that one is a part of. Though Keniston was speaking for America and Europe, the anxieties of 20 somethings over love and marriage in this part of the world is not a matter to be brushed aside.

Placed anywhere between late teens to late 20s, this group, hailing from various socio-political and economic conditions of the Indian society, are at loggerheads with almost every structure around them.

Be it the question of ‘making adequate money’, ‘that ideal career choice’ or gaining the ‘right qualification’, most youngsters across this spectrum in India negotiate these struggles on a daily basis. Further, belonging to varied classes, castes and religions has not been entirely helpful in shaping their decisions. Add to it the anxieties over love, marriage and societal approval and the concoction turns potent, complex and tangled in various ways.

“My ‘Tam Brahm’ family is very liberal and progressive in many ways. They have always let me take my (own) decisions regarding a career and (even) otherwise. Apart from (the freedom) to choose any person outside of caste and religion, they have also let me manage and screen my own matrimonial profile,” says Preeti Ragunanth, 26, a PhD scholar of communications from Hyderabad Central University.

“The only rule is to have a ‘level playing field’ — similar family background and education. Because of my solitary phd life and ageing parents, I took this step of exploring alternate options of finding a partner myself,” she adds.

While Preeti’s narrative seems fairly linear and planned, the thought process of those hailing from lower-caste and income backgrounds, attempting to juggle the traditional and the modern, in matters of the heart, is subjective.

“You are at their (parents) mercy, whether you like it or not. I was in love with a Dalit boy over a period of nine years. While I kept studying in a different city, he continued his job at a shop. When my parents got to know (about the affair), they were primarily furious about his caste and his job,” says *Srinanda Singh (name changed), 23, an engineering student at iit, Kharagpur.

“I fought for the relationship but it sucked the life out of me. After a while, the relationship died because I was still living with my parents and hence, I had no say in settling for a partner of my choice,” she adds.

According to the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS, 2014) conducted by the National Council for Applied Economic Research (NCAER) and the University of Maryland, only 5 percent of urban Indians have claimed to have an inter-caste marriage.

While this percentage was only slightly higher than the statistics received from rural India, the data presented by the National Family Health Survey (2005-06), reveals the general reluctance of families towards Dalits in inter-caste marriages.

On a parallel note, the estimates around inter-religious marriages in India were also equally weak, according to a research conducted by Princeton University, New Jersey, US (2013). Only 2.1% of marriages across India were found to be inter-religious.

“My parents and grandparents have had love marriages. So, that is a kind of a norm in my family. But if I love someone outside my religion, it would take some time to convince (them). For instance, my ex-boyfriend was part-Muslim and they were not very convinced about him. But, I think they had more reservations about the person that he was, than about his religion,” says Rohini Dutta, 24, a PhD scholar at the Indian Institute of Science (IISC), Bangalore.

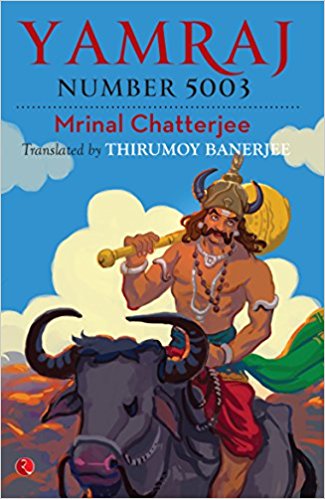

Photo: AFP

Although the question of choosing partners, either according to societal norms or against them, is well-known and well-explored, there has been virtually no effort put into understanding how the question of legitimacy — through law, space for cohabitation and personal struggles — shapes the average Indian youngster’s views on intimacy.

For example, the experience of an inter- religious live-in couple hailing from Kerala has been anything but conventional. “While my spouse, Naseera, faced a lot of turmoil from her family, I did not have to go through much at home. From a young age, I have been ‘politicallyresistant’ at home. So, my parents were well-aware of my general nature,” says Subin, 25, a journalist. He has been in a live-in relationship with Naseera for three years.

“When there were some tough circumstances (created by) her side of the family, we signed on a legal document. Otherwise, there has been no formal registering of the marriage. Personally, I feel there are exceptional cases, of those who veered away from the ‘normal’. But most people of our age think and choose within the boundaries of caste and religion even when they ‘fall in love’,” he adds. In some situations, it is the space of cohabitation that defines the longevity of a relationship. For instance, the unavailability of affordable localities and housing areas for couples in love (same sex and otherwise) or for live-in couples has been taxing.

“It is (also) a question of where you stay after you decide to go against a societal structure. The survival of what you share with your partner also depends on the neighbourhood. The locality that I stay in (Munirka) is close to a campus and hence, student-friendly. So, a landlord intervening in our personal life or asking questions on our marital status was not a concern. Otherwise, I think, only very high-income neighborhoods provide the space to do as one pleases,” says Pratik Kasimpilla, an M Phil student of Delhi University.

However, in it cities like Bangalore, the cosmopolitan culture has played a big role in letting youngsters explore intimacy quite freely.

Though that has earned the city the reputation of being ‘wayward’, to many others, the city is relatively ‘warm’ and ‘peaceful’. “I feel that a lot of people (including parents) here are open to the idea of their children choosing their partners now. This city lets you be and does not stuff caste/religion/culture down your throat. As I result, I see many (of my) friends explore options of living together before they decide to tie the knot. In a sense, a lot of people are their ‘normal selves’ here,” says Abhilash Alex, 25, a software developer.

In October 2014, when the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad wing of the Delhi University campus, had launched a campaign targeting live-in relationships on campus, the organisation had reportedly made statements on how violence against women was a norm in live-in relationships, since these relationships were ‘unaccountable’.

Although the statement was onesided, given the equal possibility of the occurrence of violence in a marital relationship, the notion of accountability had more to it than what met the eye.

“In our locality, there was a tussle between our neighbours that turned violent. When we called the cops for help, they were not keen about filing a case. Instead, they were more bothered about the women in the room. It only shows how one cannot seek help in any unfortunate circumstance when one is not ‘legal’,” says Kasimpilla.

At present, there is no law that deals with the concept of live-in relationships. While the Protection of Women from Domestic Violence Act, 2005, covers certain concerns related to benefits for women, the general nature of Indian law barely reflects such modern challenges.

Sometimes, the nod of acceptance for ‘the youngster with a job and carrying a wad of money’ circumvents societal norms. In such ironic scenarios, power and money propel parental figures to transcend the ‘norm’.

“A cousin brother of mine was 19 when he fell in love and got married. Not only did my family have no issues with his age, they also helped him fake his papers to look old enough. All they cared about was the bride. She was the daughter of an ias officer,” continues Pratik.

In his column titled ‘No Escape From Each Other’ published in India Today, Ashish Nandy, eminent Indian political psychologist and social theorist, wrote how cross-cultural, modern marriages in India were becoming increasingly claustrophobic and contractual over time.

Some of the factors that Nandy had enumerated to explain this phenomena was the initiation of the nuclear family system, women’s entry into the professional job sphere and the reconfiguration of sexuality in everyday life.

While these factors may be true, the lack of estimates around the number of youngsters falling in love, thwarted in love and ‘told’ to stay off love marriages (cross-cultural or otherwise) and live-in relationships by parental or state authorities reveals a condition of societal stagnancy.

Equally alarming is the lack of an honest dialogue around sexuality and politics between this potential, talented, curious group of Indian population and society. Though reductive, this dialogue of a hipster in a popular Malayalam movie is not far from the truth.

“I’ll tell you why I don’t follow rules. If you get a degree, they would ask for a job. When you get a job, the question would turn towards marriage and then, when you get married, they would ask about kids and the cycle would continue. In other words, we are all living inside a pressure cooker and we may explode soon if we live (according) to the expectations of society”.